Should Young Athletes Specialize in Sports? Prep Families Weigh In

September 25th, 2025

Lionel Messi joined FC Barcelona’s youth academy at 13, famously signing his first contract on a napkin. Simone Biles was a world champion gymnast by 16. Bryce Harper appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated at the same age, fast-tracking his way to the MLB as the No. 1 draft pick in 2010.

With examples like these, it’s easy for parents of gifted young athletes to dream big. They invest in club teams, private lessons, and off-season camps, believing the only path to success is specializing early and working harder than everyone else.

Why Specialization Can Backfire

Dr. Nirav Pandya, pediatric orthopedic surgeon at UC San Francisco, has studied the impact of early specialization. His findings show this: professional athletes who played multiple sports in high school perform better and stay healthier than their single-sport peers. Looking at a decade of NBA first-round draft picks, Pandya found that multi-sport athletes played in 19% more games, had higher efficiency ratings, and were twice as likely to earn awards. Similar patterns show up in the NFL, NHL, MLB, and Olympic sports.

The risks of specializing too soon are significant: overuse injuries, burnout, and stunted development of diverse motor and processing skills. The youth sports industry’s $40 billion price tag, according to the Aspen Institute, only fuels the push for kids to train year-round.

The View from the Sidelines

Cathy Walters, Sandia Preparatory School’s athletic trainer with more than 30 years of experience, sees the effects firsthand.

“So many sports are now year-round without time for athletes to recover,” she says. Some parents, eager to get ahead, hide extra training and treatments from coaches, risking their child’s health. “If they are too tired from yesterday’s off-site session, they’re no good to the in-season coach. Parents are taking children to multiple providers and even resorting to non-FDA-approved treatments.”

Walters notes that single-sport athletes often lack broader skills: “Swimmers may have poor hand-eye coordination. Baseball players may struggle with footwork. Fitness varies dramatically from sport to sport.”

Student Perspectives

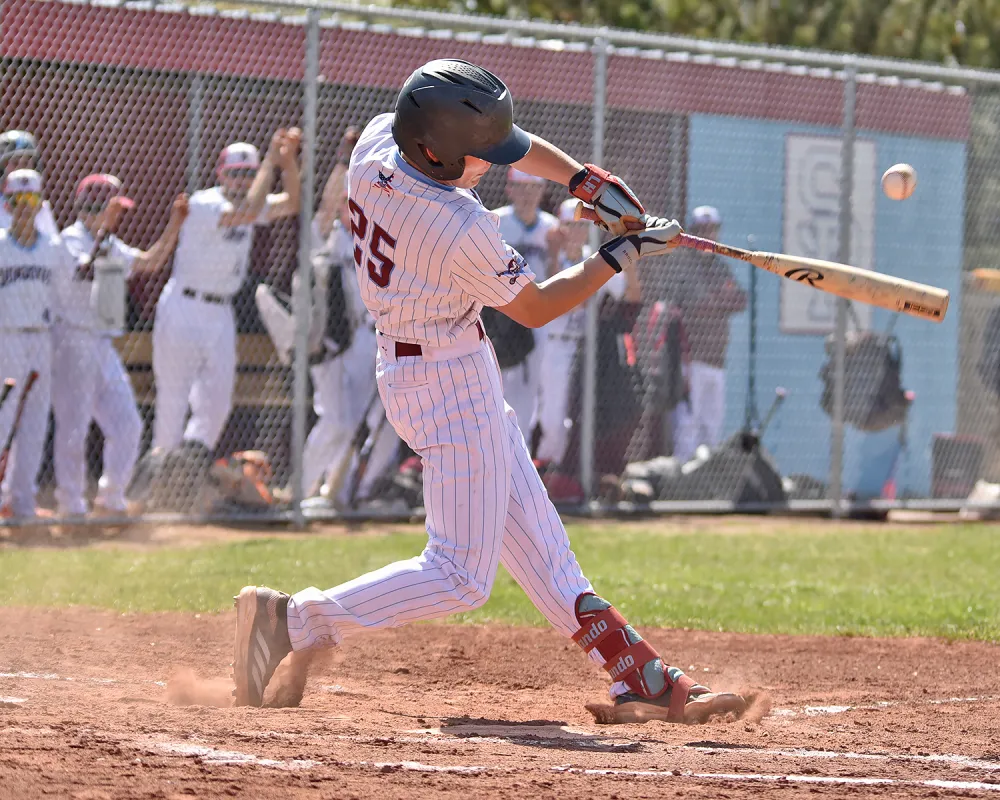

Prep junior Logan Lemons ’27 is one of those students. He hopes to play college baseball, but also plays varsity basketball.

“When I just played baseball, I started burning out and even injured my arm,” he says, describing a UCL strain that nearly ended his career. “Switching things up keeps sports fun, keeps me motivated, and makes me stronger.”

He’s noticed a shift in coaching attitudes, too. “At first, club coaches pressured me to focus only on baseball. Now, more of them say, ‘Be an athlete as long as you can.’ They see the longevity multi-sport athletes have.”

That longevity is critical. Many young baseball players with Division I commitments spend as much time rehabbing from Tommy John surgery as they do training. The procedure—common among pitchers aged 15-19—can take 12 to 18 months of recovery.

Sandia Prep senior Amelia Martinez ’26 has lived the other side of the story. She dedicated herself to softball, training year-round, playing not only on Prep’s team but also competitive travel teams and chasing a college spot—until recently. “What used to be exciting and motivating started to feel exhausting,” she admits.

She no longer plans to play softball in college. Stepping away was hard after years of defining herself as a softball player, but it gave her room to reevaluate. “I still love the sport, but I don’t want it to define my future anymore.”

Parents in the Middle

Logan’s parents, Candice and Jason Lemons, faced the same dilemma many families do.

“There were times we wondered if we should push specialization so our boys didn’t ‘miss the boat,’” Candice says. But ultimately, they encouraged Logan and his older brother Lucas to play multiple sports. Lucas went on to play college baseball in Wisconsin.

“Socially and emotionally, my boys made friends with different interests,” Candice explains. “They learned to adapt to different coaching styles and situations. That made them more well-rounded—not just as athletes, but as people.”

Walters’ daughter, Carissa Martinez ’21, was a high-level gymnast, eventually competing at both D3 and D1 schools. “Gymnastics was my daughter’s sport from a young age, but I required her to have an off-season/time away from training, especially after competition season,” she explains.

During elementary and middle school, Martinez played several other sports, and at Prep, she ran track. “I think this was crucial to her successes,” Walter says. “She had great athletic ability across the board, which I think did her a lot of good at her own sport regarding self-awareness, coordination, courage, and perseverance.”

Walters insisted on re-evaluating each year whether Carissa wanted to continue the grueling sport. Though she has no regrets, Walters says her daughter is having to manage lingering aches and pains from all those years of competing.

Lessons Learned

Looking back, Amelia Martinez wishes she had done things differently. “I think if I’d explored more sports, I wouldn’t have burned out so quickly,” she says.

But she also sees her experience as a step forward. “Being a successful athlete isn’t about grinding year-round in one sport. It’s about balance, passion, and staying physically and mentally healthy.”

Walters points out that young athletes need to make sure they develop an identity as more than just an athlete so they can move forward when their sports careers are over. “In the military, after serving, they debrief you,” she says. “Sports? Not so much. Who are you?”

The Bigger Picture

From Messi to Biles to Harper, prodigy stories capture the imagination. But for most young athletes, specializing too soon may close more doors than it opens.

Research, coaches, parents, and students increasingly agree: long-term success comes from balance, not burnout.

More Sundevil News

Nov6Mountain Bike Team Captures Second Straight State ChampionshipThe Sandia Prep Mountain Bike Team succe...See Details

Nov6Mountain Bike Team Captures Second Straight State ChampionshipThe Sandia Prep Mountain Bike Team succe...See Details Nov5Prep Collaborates with Landmark for The Sound of Music Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kitte...See Details

Nov5Prep Collaborates with Landmark for The Sound of Music Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kitte...See Details Oct28Prep Earns A+ School Rating Sandia Prep recently once again earned a...See Details

Oct28Prep Earns A+ School Rating Sandia Prep recently once again earned a...See Details Oct22Head of School Featured in Albuquerque Business First Sandia Prep Head of School Heather B. Mo...See Details

Oct22Head of School Featured in Albuquerque Business First Sandia Prep Head of School Heather B. Mo...See Details